Jen Michalski

Of the two of you, you were always more morose. In fact, you could never remember a time, exactly, when she complained about anything—her parents, her job, her friends. But she was delicate in a way, a lack of permanence, a lack of tenaciousness, but still tough, like the way celery is impossible to break apart because of all those fibrous strands, and it never, ever rots, ever, even though you’d buy it and it’d sit in your shared refrigerator for months, waiting for you to begin your diet, because you were always the chubby one, always sturdy, Eastern European dough girl, and she was the thin one, the one who people always asked whether she was a dancer, a ballerina, a model. You were more like the celery, and she was not food at all, maybe rice paper, which is technically a food, although transparent and lacking mostly in nutritional value.

She was so nice. And that’s what makes it so difficult for you to understand. Even when she broke up with you, she framed it in such a way that you didn’t feel so bad, that she wasn’t good enough for you, that you deserved better, that you should examine your options. And when you think about it, she was probably right, not because you are some great catch but because you never really knew her. You wondered if anyone ever did. You thought maybe she would let you in, that you would get to know her, but even at night, after you kissed her and ate her out and fisted her and licked her breasts and stroked her thighs, you asked her what she dreamed about, and it was always that she was in French club but realized she couldn’t speak French or that she missed the ferry back from the Vineyard and got fired.

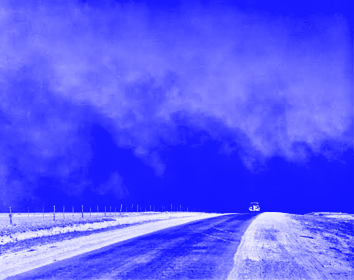

You were looking for dirt that you could rub between your fingers, a grit that would catch under your fingernails, take days to scrub out.

She had things. She went to all the camps, French and drama and some sort of Jewish religious camp with girls who went on to become psychologists or star in cable television comedies. You always went to parties with her, ones you wouldn’t have normally been invited to because you were Polish and lower middle class and your mom signed you up for swimming lessons at the Y and the summer reading challenge at the library because there was nothing else to do in your neighborhood except get high behind the 7-11, except smoke pot and listen to hair metal bands. You’d stand by the serving spread and sample smoked trout on crackers the size of half dollars and she would be in the middle of the room, head arched back, laughing with someone she went to school with at Smith, her doubles partner from day school, god knows what she talked about and you thought these people didn’t know her either, because they were so transparent but maybe she was, too, and when you complained about them on the ride back to the apartment she’d laugh and touch your thigh and say, “they’re just friends. You’re my girlfriend.”

What privileges were bequeathed to you as girlfriend, you’re not sure. You saw her without her makeup on, sure, but was it really a terrible secret that she read Vanity Fair on the toilet? That she ate almost nothing, that jar of Nutella that she’d spoon while watching the late night talk shows, and cereal? That when she farted she laughed in apology, and it was almost too cute? There was nothing, on the surface, to suggest anything terrible, and maybe that’s why you found yourself looking through her desk, her computer, her purse, the trash, when she was on the phone or outside on the balcony, having her once-a-week cigarette. You were not looking for evidence of an affair, or bulimia, or membership to a terrorist cell, just something. You were looking for dirt that you could rub between your fingers, a grit that would catch under your fingernails, take days to scrub out. Something that would leave a mark.

She said you were too clingy, too questioning, too suspicious—not everyone had to be damaged, at least damaged in a way that rendered one non-functional. Not everyone had to be difficult or deep or mysterious. Not everyone had to be like you. But everyone had to be someone, you thought, and not like someone. Not a person on paper. A real paper, with pulp and grain, and not a Xerox. But she made you laugh, the silly songs she made up about the cat, or how her trip to the grocery store, uneventful for most, became the most-fucked-up-thing ever because she ran into that guy she used to do improv with when she graduated from college and he was buying vaginal cream for his girlfriend because she was too embarrassed and how he quizzed her on the finer points of the 3-day versus the 7-day and there was that kid in the aisle with the mom who freaked out because colon cleanses made their way into the conversation and then she left her keys, somehow, in the produce section, right by the melons, and it took her an hour to find them, isn’t that crazy, because neither of us eats fruit, right?

There was nothing to suggest she was unhappy or that she missed you.

Sometimes when she’d sleep you’d watch her, and deep in dream she would frown, or flinch, and you questioned her when she woke up but she said you were being paranoid, that she couldn’t even remember what she was dreaming about. She would then ask about your dreams and you’d had a particularly disturbing one, how you sat with your dying grandmother and she smelled, she smelled so horribly of decay, and you’d known it’d been weeks since she showered, she could barely move, but she put her head on your shoulder, and you knew she missed being touched because no one ever touched her anymore, and it wasn’t her fault, that she was so gnarled and foul-smelling and immobile, her eyes milky and weepy and you realized this woman was a child once, a girl, a woman who fucked, who loved and hated and regretted, and all she could do was put her head on her granddaughter’s shoulder while her granddaughter tried not to breathe.

She was clever that way, always turning things back to you, like a psychiatrist, and maybe you were so fucked up yourself it took you a few years to catch on, to recognize this game of deflection and to call her out on it, and why didn’t she dream, why wasn’t she ever unhappy when you could see it sometimes, in the briefest of moments when she thought you weren’t looking, the way she frowned and chewed her fingernails, then she’d freak out in the car on the way home from the birthday party because she thought she was mean to someone but she was never anything but nice to everyone, always complementing, always laughing, always caring, in such a way that no one ever thought she was fake, and if they did, they would never say it aloud because they’d look petty, a bitter sister, and it was that way, the way they felt for a minute, that you felt all the time, that she was a mirror that showed you all your faults and when you reached out for her it was your own hand coming back toward you, your own warts, your own insecurities.

You were thankful she stayed with you. It became easier—imperative—after a while, for your own sanity, to believe in her, believe she was happy, successful, beautiful—and she was beautiful and successful, of course–and that she would make you a better person by association. And you tried. You tried to iron that shit out—all your wrinkles, all your neuroses, your disappointments, your snark. You tried to be like her, but it felt like scooping everything out of yourself and tossing it into the laundry basket before you left the apartment. You felt nothing, and that didn’t make you sad, so maybe that was good. But it didn’t make you happy, either.

When she broke up with you, you took it badly. You blamed yourself. You could never rise to whatever level of Zen she had carbined herself to. You were afraid of such heights. She said you’d changed, and when you pointed out that you had, that you tried so hard to be like her, she said she liked who you had been. But you weren’t sure whether you had liked who she had been, because she’d never been anybody. And that wasn’t the point, because she dumped you, and in that equation, the dumped is always at fault.

You moved to this city, where you are now. It folded around you like your grandmother, and it was something you got used to. Its scents, its dirt. It was you. What you knew. But you stayed friends with her on Facebook, and she stayed in that city, and had those friends, that cat. There was nothing to suggest she was unhappy or that she missed you. And no one told you that she did it, you just found out because of the Facebook posts people left on her page. Hundreds of them. In hysteria, in shock. But why she did it—no one ever asked you. If they thought you were the reason why she did it, you would never know. They never spoke to you after the breakup. It wasn’t mean or spiteful; they just receded, like waves, back into their massive, glittery, transparent ocean in which you, of heft, of gravity, always flailed, always felt like you were drowning.

How could you live with her for so long—four years—and make her come, watch her sleep, buy groceries together, how could you not know she would do something like that? How could you not see she was unhappy? And if you were with her for so long, how could she not tell you? How could you not know someone at all? Why did you stop digging, weren’t you supposed to find all the poop the dog had left in the long grass in the yard, before you step in it, before someone else did?

You are not responsible. You know this. But you lie awake at night and think about the dreams in which she had forgotten how to speak French, got stranded in the fucking Vineyard—would have been out of bounds to suggest she speak to someone, take something, go on a journey of self-discovery, on such flimsy evidence? And what did she want in you—did she want to live vicariously through your faults, your moods, your failures, her head on your shoulder, with her hair that smelled like Paul Mitchell, her breath that always smelled like gum?

There are things that you keep in your apartment in your new city—they were of no great importance to your relationship, exactly, just some things you have kept after your life with her. A CD she made you of French chanteuses that she gave you after your second date. A rubber bat she hung on the mirror of your car one Halloween morning. A necklace she always wore but never told you its origin—a broken crystal in a handmade wire setting. Had someone made it for her? Had she made it herself, in summer camp? You took it thinking she would contact you, ask you if you had stolen it, demand you give it back. It was important to her, and she could not live without it. She never did. You stopped wearing it after a few weeks because the crystal dug at your breastbone, left a little red welt. The little wire scraped your flesh. You tried to remember whether it had agitated her skin like it had yours. Had she never taken it off, even to shower, to sleep? Did she move it from one side to the other, trying to find where it irritated her the least? And if it bothered her so much, and how could it not, with its impossible craftsmanship, why didn’t she take it off?

You thought about returning it after you found out what had happened, maybe sending it to her mother, her sister, even though you’d only met them once. She said she was on good terms with her family, adored them, but you never visited them, nor them you, and they never called, to your knowledge. You had always just assumed it was because they didn’t like you. You still thought it should be returned to her, wherever it was she wound up—but those details were never offered to you. A few weeks after it happened, someone deleted her Facebook and her Instagram. Or you were deleted. Does it matter which one it was?

The necklace, at least, is still yours, although it never was. It’s all you have and you can’t get rid of it. Not because you want to keep it, but because everything needs a word, an answer. When your new girlfriend moves in, it hangs in your bedroom window. You never offer its origin. Most of the time it’s just there, like a crack, a nick on the dresser, that you are aware of but somehow stop seeing. Although sometimes the sun catches the crystal, refracts the light, and spreads little rainbows on the wall. They are always changing their places. You never know, where things will be, from moment to moment.