Jayne S. Wilson

A better person, she will think later, would worry about him. And maybe she does, but in a way that she can live with.

She will enter his room, take in the smell of crusting dust and stale breathing with a fresh comforter and two pillowcases folded over her arms, and notice the creases on the yellowing sheets and how empty they seem without the spindly arms and legs they have sunken around. She will tuck her hair, gray roots reemerging, behind her ears and think that he is probably in the garden, must have pulled and forced himself out of bed and down the stairs to sit outside on the chair shaded beneath the oak they’d planted together some decades ago on their first weekend in the house, toasting later with sweat on their foreheads and above their lips to the years and the firsts in them that then still had yet to ensue, and that mostly confused him now, tethered somewhere behind his eyes on the same frangible thread as songs he didn’t know he knew, movies he couldn’t be convinced he’d seen, and the faces of neighbors and friends, and her face too, that he had to be reintroduced to, their existences like items that had rolled, one by one, from atop a dresser and into the dark, small space against the wall behind it, lodged and invisible.

But when she steps outside with his lunch tray poised between her hands, she will find that the chair, too, is empty.

But when she steps outside with his lunch tray poised between her hands, she will find that the chair, too, is empty. She had missed the subtle creaks, softer than before, of his weight against the old wood on the staircase, the shifting of dust from the bannister to his pruned hand while she kneeled in the basement an hour earlier pulling laundry from the dryer, and the empty dish on the hall table where the car keys had been. And when she does notice, when she does see, there will be unease, like a pinch of the skin, but only for a second before she’ll think of him remembering the steps to the door and the color of the car, and she will not be able to keep herself from hoping, instead, that he loves the push of his feet against the pedals and the feel of adjusting his rearview mirror, peering into it for blind spots and cautionary distances, perhaps seeing her.

The car door was heavy, the leather thick, the steering wheel unexpectedly stubborn, but the radio dials were tuned to where he hoped he could sing along to a Tom Petty song…

And all this she will not know: how he had strewn his pajamas upstairs on the floor of the bathroom with the careless grace of a teenager running late; how the bottoms had almost slid down on their own as he stood, how the buttons on his shirt had an easy give; how even with the keys in a different bowl on a different table, the second family car had been an easy take; how he imagined his parents at work and no one else to notice him slip out with no clothes on his back when he aimed the car out of the driveway and toward the lake just at the edge of town, a flash of blue he could almost see between trees.

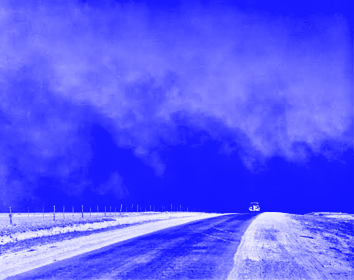

The car door was heavy, the leather thick, the steering wheel unexpectedly stubborn, but the radio dials were tuned to where he hoped he could sing along to a Tom Petty song, with the windows down to let a fickle summer breeze tease his hair and the sun warm the eager goosebumps from his bare skin. The rest of the baseball team’s seniors were, like him, barreling from their homes and climbing into their parents’ cars, or cars that had been given just days before as graduation gifts, in nothing but sneakers, stifled laughter and palpable heartbeats soundtracking their ride to the senior picnic at the lake to answer the rallying call of team captain, Joey Guadagno, who wanted to one-up the football team’s “piss-poor” senior prank of super-gluing all the school doors shut by having them all streak their entrance to the picnic – a line of boys with farmer’s tans hooting with the mania of summer and a future that was nothing but theirs.

The skin on his thighs lifted from the seat like warm rubber and he imagined, vivid as memory, the stupid-brilliant lot of them dodging blankets and coolers and scandalized girls and Principal Hadley, who later, when they were dressed in the gym clothes they’d pre-packed in Joey’s car, would give them a lecture on decorum, saying, “I guess you fools are proud of yourselves,” then asking them what in the hell there’d been to gain, because he couldn’t see it, that there’d been only Maggie amongst the girls, laughing as she tucked her hair behind her ears, and that there’d been the pushing and daring of distance, and the taste of endless sunlit air. And so who could feel remorse?